RICK

BUILDS A MORRIS CHAIR

Several years ago, at a time when Elaine and I were

considering designing a new house, I became very interested in the Arts and

Crafts movement, and the furniture associated with it. The Arts and Crafts

movement actually originated in England in the late 19th century, and was

brought to America through the works of such artisans as William Morris,

John Ruskin, Nicholas Jenson, Philip Webb, and later by Gustav Stickley and

his brothers, and by brothers Charles Sumner Greene and Henry Mather Greene.

This movement was a backlash against industrialism,

an attempt to return, at least philosophically, to the day of skilled

craftsmanship, and the production of beautiful pieces one at a time.

As both a writer and a woodworker, this concept

strongly attracted me.

"Have nothing in

your house that you do not know to be useful, or believe to be beautiful."

-William Morris

The chair pictured above is one example of the

realization of the Arts and Crafts philosophy. While it is called a Morris

Chair, in that the original concept was developed by William Morris, it

really is an interpretation of Gustav ("Gus" from now on) Stickley and his

brothers Leopold, Albert, Charles, and John George.

Together, they brought the Arts and Crafts movement

to a new American culture, through their furniture, and through the magazine

The Craftsman, which Gus Stickley founded and edited beginning in

1901. In all their work, they attempted to embody the Craftsman philosophy

as stated by William Morris (right).

The Arts and Crafts movement is more than just a style

or a technique. It is a way of thinking. It's about taking the time to

assure that everything your hands produce is as well-crafted as you can make

it. There is a Zen quality to the movement. Properly executed, a fine piece

of Arts and Crafts furniture, pottery, wallpaper, or even an entire house,

should not only please the eye, but also should impart on its user a sense

of peace and serenity.

As envisioned by the Stickley brothers, Arts and

Crafts furniture was intended for the masses. It was fine furniture crafted

for the middle class.

In order to provide as many people as possible the

benefits of Craftsman thinking and workmanship, the Stickley brothers began

to incorporate factory methods--including machinery--to construct the basic

components of his pieces, which were then handed over to skilled craftsmen

for assembly, fitting, and finishing.

This tradition remains with us today, as

exemplified by the work of such popular carpenters as Norm Abram of The

New Yankee Workshop.

A couple of years back, I remodeled my home office. At

the time, I installed a cheap papasan chair for reading, and always intended

that it would be temporary. In the back of my mind was a plan to replace it

with something beautiful, more befitting the room which serves as both my

personal library and the place where I create my books and short stories.

On this page, I plan to follow--step by step--the

process of crafting a Stickley-style Morris chair, as illustrated above. The

picture at the top of the page is from the plans I'll be using.

This chair has all the hallmarks of the height of

Stickley's craft. The bowed arms, which will be constructed by laminating

thin layers of oak over a plywood mold, provide a restful place for the

reader's arms. The back cushion reclines to allow the owner to take a

restful nap, and raises easily to a reading position. This chair is the

perfect place to lounge away a cold, snowy winter afternoon. I can't wait to

use it as the final component of my perfect home office.

As with other projects I've outlined on these pages,

the wood that I'll use for this project is classic and traditional. Stickley

made most of his furniture from quarter-sawn white oak (Quercas alba).

Oak, besides being heavy, is very stable in use, and when cut on the quarter

it displays a remarkable medullary ray fleck. It is also relatively easy on

machine blades as compared to other dense woods like, say, jatoba or some

rosewoods. Finally, it's just traditional.

Quarter-sawing is the process of milling logs in a

way that keeps the growth rings perpendicular to the width of the board.

While, ideally, the growth rings should be 90 degrees to the plane of the

board, a deviation of up to 30 degrees is usually acceptable. Cutting boards

on the quarter helps to prevent warping and cupping of the boards as the

fibers expand and contract in heat, cold, and humidity.

One reason that white oak is the traditional choice

for Arts and Crafts furniture is its natural beauty. One peculiarity with

white oak is its tendency to develop "medullary rays". Within the heartwood

of the trees, some areas of wood have a different cellular structure. When

sawn on the quarter, these areas of medullary rays reflect light differently

the other heartwood does. These rays radiate from the center of the oak log

to the bark, like a lighthouse beam from the lighthouse itself. When the log

is quarter sawn, the rays are cut at a very low angle compared to slab

sawing, and this low angle shows off more of the rays' surface. Also,

medullary ray flecks take finishes differently than the rest of the

heartwood, so the finished piece takes on a beautiful variegated figure. Of

course, it takes considerably more effort to quartersaw boards, and it

results in less usable board feet. For that reason, quartersawn white oak is

more expensive than slab-sawn lumber. It's worth it, though. The main point

is to try to use as much of every board you have as possible, in order to

minimize waste. White oak isn't endangered at all, and supplies are fairly

plentiful, but why waste the money by tossing pieces of it into the dumper?

What I don't use for the chair will be saved for other projects.

Of course, if you've been reading some of my other

woodworking pages, you know that I like to start out with rough-sawn boards.

First, they are cheaper. Second, I always enjoy the process of milling them

to proper size ("dimensioning"), and seeing what kind of figure is revealed

underneath the surface as it smoothes out.

Here is the first quarter-sawn white oak board I'll

be using. I picked all of these boards up from Woodcraft in Charlotte.

I don't want to mill the entire board yet, because

different pieces of this Stickley-inspired chair project will have different

widths and thicknesses.

So, the first step is to rip and crosscut this

larger board into smaller pieces.

The first pieces I'll be building are the legs. Of

course, there are four of them, but in the case of this chair they each will

require four pieces of wood. Remember that business earlier about the

medullary ray flecks? In order to maximize the beauty of the chair, I want

all four sides of each leg to display the rays. Each leg is 2.25" square.

Finding boards pre-dimensioned to this size is pretty difficult. That leaves

me with several options. The first option is to laminate two or three boards

together to make one board that is 2.25" square. However, that sort of leg

would only display the ray flecks on two sides. I could possibly cover those

non-quartered sides with some quartered veneer, but that would create the

possibility that the veneer might delaminate (pull away from the leg) in the

future.

The obvious answer is to use quadrilinear legs.

Here, I'm drawing a line down the midline of the board.

The next step is... What's that? You don't know what a

quadrilinear leg is? Well, why didn't you say so? Happy to tell you.

A quadrilinear leg is constructed from four

individual boards that are glued on edge, so that each one displays a

quarter-sawn face and its gorgeous ray fleck.

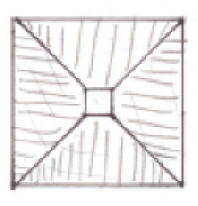

There are several ways to do this. One way is to

simply miter the edges of the four boards at a 45 degree angle, and glue

them together (top pic at right). This tends to produce a poor glue joint,

however, and may come apart at some point in the future.

Another way is to use some kind of interlocking

joint, that will increase the gluing area and limit movement of the joint,

such as the pic in the middle at the right. This is accomplished with a

special router bit, and can produce a stronger joint.

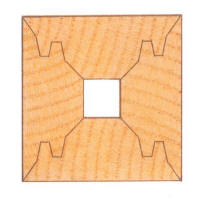

In our case, however, I'll be using a somewhat more

complicated joint (bottom picture, right). I'll show you how I make it

later.

Thanks, and a tip of the hat to

The Gus Guild website for these three pictures!

Okay! Now that I've marked the midline on my first

white oak board, I need to rip it into two pieces, hopefully of roughly

equal width.

For this chore, I will turn to my favorite tool, my

trusty 14" Jet band saw.

For those who aren't acquainted with woodworking,

"ripping" a board means to make a cut alongside it's longer plane, usually

with the grain. If you saw across the short plan of the board, usually

across the grain, then you're doing a "crosscut".

There is also resawing, and we'll be doing some of

that later one, but it will be easier to explain it then, when I'll have

pictures.

By the way, this is the last time I used the band saw

to rip a board on this project. While it worked okay, oak is a tough wood,

and there was some deflection in the blade, which meant that the cut wasn't

totally straight. It was relatively easy to fix, but on the rest of the legs

I used my table saw, which made much straighter cuts.

Now I turn to my bench planer. As I've said before, I

am always just a little scared when I use this machine. It revolves at

something like ten thousand RPM, and the two planer knives inside could turn

a hand into ribbons in less than a second. On the other hand, it really gets

the job done.

First, I pass the boards through on their edges, to

get a good straight joining edge. Then I pass them through on their flats.

The goal is to get the boards to a little over 3/4 inch in thickness, and

about 2.25 inches in width. I check the precision of the dimensioning using

my digital calipers. It's a little hard to see the numbers in these

pictures, but I leave them a little proud, because I'll still need to smooth

the legs once they are quadrilinearly jointed, and this will reduce their

size by roughly the amount that I oversized them.

Each of the front legs is about twenty-two inches in

length. I dimensioned each of these boards in four-foot lengths. Now it's

time to cut them in half. After marking their mid-length, I pass them

through the table saw.By the way, I

suppose you could also build this chair out of red oak that you can buy

pre-dimensioned at your local DIY home store (Lowes, Home Depot, etc.).

They've already done all this work for you, and once in a while you can

actually run across quarter-sawn pieces there.

Slacker.

And here are the four pieces of the first front leg.

Notice how, now that they've been planed and smoothed, you can see the

medullary ray flecks? Believe me, this picture does not do these boards

justice. As you move around them, the changing light makes the flecks jump

out as they refract light differently. This is going to be one beautiful

leg!From roughsawn board to the four leg

pieces took about an hour and a half of work. Now I only have to do this

three more times, and I'll be ready to move on to the next step!

I'll spare you the details on dimensioning the

other three legs, and show you how I prepare them to be jointed.

Now that I have the sixteen pieces of the four legs

cut and dimensioned, it's time to rout out the interlocking cuts that will

hold them together. I bought a special router bit from Rocker, designed

specifically to cut the joints for the legs.

Here, I'm running one of the leg pieces through the

router. Because the router bit is so large, and white oak is a little

stringy and brittle, I have to take it very slowly to prevent tear-out.

Also, for those of you familiar with routers, this

is one time you ABSOLUTELY DON'T want to prevent tear-out by using a

climbing cut (or pushing the piece into the cutter in the direction of the

rotation. This bit WILL grab the piece and fling it across the shop. It

might even impale it in a wall. Don't ask me how I know this.

Here is a test fit of the four interlocking

quadrilinear pieces of one of the rear legs. Note that there appear to be

some gaps here and there in the joint. This is due to the tear-out and

chipping I referred to in the previous slide. It's not a problem, since the

only part that will be seen in the finished product is the outside, and

those joints look pretty tight.

I'll be gluing these legs using an expanding

urethane glue, which will fill these gaps.

The real problem here is that big old gaping hole

in the middle of the leg. Later, we'll be cutting mortises in this leg and

running tenons into it. You can't join wood to air, so we need to fill this

gap. That's the next step.

Here are the filler bars for the legs. As I said

before, the primary benefit of using quartersawn white oak is its beautiful

medullary rays and flecks. Because quartersawing is not as economically

efficient as rift sawing, the wood it pretty expensive, too.

There's no point in using quartersawn white oak for

applications where the face is not visible. In the case of this chair,

I've decided to use red oak wherever the wood will be hidden, or only the

end grain will be visible. Red oak is renewable, relatively cheap, and you

can buy all you want at the local Home Despot.

For these filler bars, I just ripped them from a

two-foot long piece of red oak and dimensioned them to size using my planer.

Here you can see how the filler bar fits into the leg.

I don't actually insert it after the leg is glued up. Instead, I assemble

the leg around the filler bar, so that the leg becomes one solid complete

unit.