RICK HELMS WOODWORKING

SHAKER LIBRARY TABLE

A few months after I finished building the

Morris Chair (see the build diary elsewhere

on this site), Elaine said she'd love to have a library table behind the

couch in our den--someplace to put another lamp so she could read from her

end of the couch, and a place to put things like books, magazines, and the

endless remote controls. I thought she intended to shop for one, but soon it

became obvious that she meant I should build one. Hey, I figured,

why

not?

Compared to building a complex project like a

Morris Chair, which took me almost a year to complete working a few hours on

weekends and required several specialized bending forms and literally dozens

of mortises and tenons, a library table is actually a pretty easy project. I

figured it would take about thirty hours. I have built tables before,

including the one I write at in my home office, and the one I use to hold my

printer there. Tables are straight-forward: four legs, eight mortises and

tenons, four skirt pieces, some poplar braces, and a top. I figured I'd make

this one a little more difficult by adding a couple of dovetailed drawers.

Since most Shaker furniture doesn't use pinned mortises the way Arts and

Crafts furniture does, I was free to use screw and nail fasteners to help

hold it all together. I made some measurements, and dove in!

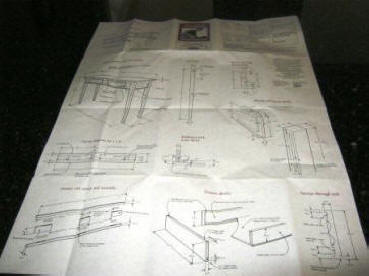

Having built a few tables already, I probably

could have done this one on the fly, but it never hurts to have some plans

to fall back on. As it happened, I already had a set that I ordered almost

twenty years ago from Norm Abrams and New Yankee Workshop--long before I

ever seriously thought about woodworking. The table I intended to build was

five feet long, compared to four feet in the plans, so I had to make some

modifications here and there. Also, his table was eighteen inches deep, and

mine was only going to be one foot deep.

When building a table, I generally start with

the legs. In this case, I decided to build the table out of sapele. I like

using sapele as a substitute for mahogany. Sapele is sometimes called

"African mahogany", but in fact it isn't a true mahogany at all. Mahogany is

in the genus Swietenia, and sapele is in the genus Entandrophragma.

They are both in the family Meliaceae, though, so they are sort

of kissing cousins. Sapele looks, works, and finishes like mahogany, but it

isn't endangered. It's also cheaper. I start out with two pieces about two

and a half inches thick to build the legs.

If you've followed some other projects I've

built, you know that I prefer to start with fairly rough lumber. You can buy

S4S (Sanded on Four Sides) lumber, but it's expensive compared to

rough lumber. I start by smoothing and dimensioning my lumber to rough size

using my thickness planer. As always, I'm very careful with this tool,

because I'm running a piece about five inches thick through, which is plenty

of room for a hand to slip in and get torn to shreds by razor sharp knives

spinning at 10,000 rpm. I keep my hands--and everything else--well clear.

Far and away, the most important tool for

this project (or any table for that matter) will be the table saw. Most of

the major operations will be carried out on it. In this picture, I've set

the fence about two inches from the blade, and I'm ripping the leg stock to

rough width. Note that I'm using two very useful tools--a push stick and a featherboard. The blade sticks up about two and a half inches from the

table, and the push stick keeps my hand far away from it. The featherboard

serves two purposes. First, it holds the workpiece against the rip fence,

giving me a good straight cut. Also, since I am not using a blade guard on

this project, the featherboard prevents kickback.

After ripping the legs, I run them through

the thickness planer again to get them perfectly square. I decided early on

to make my legs one and 7/8 inches thick, and getting them to just the right

thickness on the planer takes a little finesse with the controls. One and

7/8 inches is the digital equivalent of 1.875 inches. Is the kid good, or

what?

Rick's Woodworking Tips #23: Whenever you use

a small planer, such as the Delta I use, there is a strong chance of getting

snipe on the ends of the pieces you're planing. Snipe is caused when the

blades 'grab' the ends of the workpiece at the beginning and end of the

operation, and cut deeper for two or three inches. Because of that, I

usually cut my rough stock about six inches longer than the nominal lengths

in the plans. Then, using my crosscut sled on the tablesaw, I cut off the

sniped ends, leaving the workpiece the right size from one end to the other.

Here are all the cut off sniped ends of the

legs. I won't just toss them, because I hate to waste wood. These are the

perfect size for wood turning on the lathe, to make things like bottle

stoppers and cord pulls, and even the occasional drawer knob, so I'll toss

them into the woodturning stock box. To the right are the legs trimmed to

final length, about 29 inches.

If you've seen my other projects, you're

familiar with this tool already--my Delta dedicated mortiser. This tool

makes cutting mortises quick and easy. There are lots of ways to cut

mortises. The most common way is to drill the center of the mortise with a

spade bit or a Forstner bit, and then chisel the edges of the mortise. The

dedicated mortiser does both operations in a single pass, using a drill bit

surrounded by a square chisel. Either way works great. Using the dedicated

mortiser makes it quicker. I cut two mortises in each leg on facing

sides at the top of the legs. These will hold the front and side skirts of

the table.

One of the more enjoyable aspects of

woodworking is building tools and jigs for a specialized procedure. I

decided to build this table in the Shaker style, which meant cutting tapered

legs. This is a tapering jig I built from some plywood and poplar scrap I

had lying around the shop, and a couple of toggle clamps I bought from

Woodcraft. This is a pretty simple tool. The right edge of the jig is

straight and square, and rides against the table saw fence. The left side is

angled with a stop block on the bottom, to give me a one inch square bottom

to the leg. I clamp the squared leg into the jig, figure out where I want

the taper to begin near the top of the leg, and then adjust the fence so

that the blade hits the leg at that point. After that, it's just a matter of

running the leg through the blade.

Here, I'm cutting the taper on one of the

legs. The tapers always go on the same faces on which I cut the mortises.

Since the mortises are on facing sides of the leg, there is always a square

face opposite the taper to ride against the angle on the jig. This way, I

get a perfect taper every time.

Note again how I'm using the featherboard

to hold the jig and the workpiece square against the fence, and a push stick

to run the piece through the blade. This is important, because it keeps my

hands well away from the blade. I was born with ten complete fingers, and I

intend to die with ten.

Here's the first completed leg. Only have to

do three more, and I'm ready to move on to the next step.

The total time to build all four legs, including

building the tapering jig, was about three and a half hours. I'll stow away

the tapering jig to use again someday, and building the legs on the next

table will only take a couple of hours total.

Now I can move on to the next step,

building the table top.